Le Monete del Duce – Dux Coins

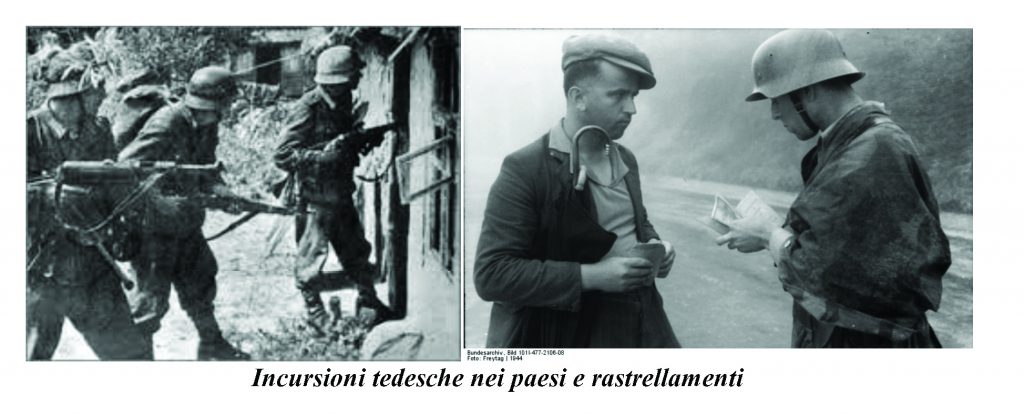

During a sunny summer afternoon Oscar and I were talking about some historical researches and expeditions that we could arrange when I started to think about the stories of my grandfather. He was taken prisoner by the Germans during the usual roundups at that time, in a village near Pisa. Men of that place were all caught and brought to work fields in Germany. He was taken along with his brother in law and they ended up in the concentration camp of Birkenau, in Poland. My grandfather said in his story that they both had a lot of luck just because they were classified as political prisoners and therefore were not killed as instead often happened to others.

Most of the detainees were Italian soldiers, many of whom were captured while they were not yet aware of the armistice and of the deposition of Mussolini by the king. The others, after the Republic of Salo’, were all forced to stay at the camps as the only alternative to fight alongside with Germans. They were also rounded up because of blackmail: so, if one soldier would not have shown his presence, the “repubblichine militias” would carry out reprisals against his family. The northern and central areas in Italy were still occupied by German troops and the new fascist units were backing the Republicans. The Italian soldiers who had chosen not to fight were all imprisoned in the camps, forced to do different types of work for the Germans, such as readjusting the power and telephone lines that had been destroyed by Allied bombing. Meanwhile, the situation got worse for Germany. The Allies were liberating Italy, advancing to the Alps, while the Russians were going eastward and the Americans westward. He also told me that the work was grueling: every day they had to come out of the camp to adjust interrupted lines, always under the control of the guards. He still remembered that one time the response given to an Italian soldier who was crying on his knees and saying “I don’t take it anymore” was a hit on the back of his head with the butt of the gun. Then he fell to the ground in front of his companions. My grandfather told me that those had become indelible images in his memory. He often ate raw nuts, tomatoes grown in human dung. But he also remembered funny situations. The prisoners often were doing their needs behind a wall surrounded by trees.

Most of the detainees were Italian soldiers, many of whom were captured while they were not yet aware of the armistice and of the deposition of Mussolini by the king. The others, after the Republic of Salo’, were all forced to stay at the camps as the only alternative to fight alongside with Germans. They were also rounded up because of blackmail: so, if one soldier would not have shown his presence, the “repubblichine militias” would carry out reprisals against his family. The northern and central areas in Italy were still occupied by German troops and the new fascist units were backing the Republicans. The Italian soldiers who had chosen not to fight were all imprisoned in the camps, forced to do different types of work for the Germans, such as readjusting the power and telephone lines that had been destroyed by Allied bombing. Meanwhile, the situation got worse for Germany. The Allies were liberating Italy, advancing to the Alps, while the Russians were going eastward and the Americans westward. He also told me that the work was grueling: every day they had to come out of the camp to adjust interrupted lines, always under the control of the guards. He still remembered that one time the response given to an Italian soldier who was crying on his knees and saying “I don’t take it anymore” was a hit on the back of his head with the butt of the gun. Then he fell to the ground in front of his companions. My grandfather told me that those had become indelible images in his memory. He often ate raw nuts, tomatoes grown in human dung. But he also remembered funny situations. The prisoners often were doing their needs behind a wall surrounded by trees.

One of those times my grandfather rushed headlong bag with content beyond the wall where a German sentry was passing…some angry curses followed and several gun shots that immediately led him to understand what had happened, and, with his pants down, he ran off avoiding reprisals. On a cold day in November they heard some news about the German position in the war and they decided it was time to escape from the camp, so he talked to his brother in law and to their three companions: “we are prisoners and we are a lots, the Germans who control us are very few. Here is the story by the newcomers and says that the situation for the Nazists has become tragic, Americans are already close to the Alps and then the Germans will have to leave the field, recede and then organize themselves on other defensive lines. If we’ll stay here the Germans will make us all out, it would be too risky on their part to leave us in life or freedom if only out of fear of retaliation on our part. We must try!”. They put into practice the well-studied escape overnight: they would have found themselves behind the wall of needs, also protected by vegetation. At the end of the wall was beginning the forest, and once reached, they would have had some real hope of saving themselves. Certainly discovering the escape would have begun a sort of manhunt but, between the risk of being taken over again, as had happened to others, and almost real death, there would been no hesitation nor proportion: it was worth still groped! And so it was that the group slipped down stealthily from the field from a hole in the net, eluding the surveillance of the sentinels, reached the woods and then started to run to the bushes and weeds, to the increasingly dense vegetation. Although exhausted and malnourished they unanimously decided the guard duties so that they could indulge in a half-sleep for a couple of hours.

One of those times my grandfather rushed headlong bag with content beyond the wall where a German sentry was passing…some angry curses followed and several gun shots that immediately led him to understand what had happened, and, with his pants down, he ran off avoiding reprisals. On a cold day in November they heard some news about the German position in the war and they decided it was time to escape from the camp, so he talked to his brother in law and to their three companions: “we are prisoners and we are a lots, the Germans who control us are very few. Here is the story by the newcomers and says that the situation for the Nazists has become tragic, Americans are already close to the Alps and then the Germans will have to leave the field, recede and then organize themselves on other defensive lines. If we’ll stay here the Germans will make us all out, it would be too risky on their part to leave us in life or freedom if only out of fear of retaliation on our part. We must try!”. They put into practice the well-studied escape overnight: they would have found themselves behind the wall of needs, also protected by vegetation. At the end of the wall was beginning the forest, and once reached, they would have had some real hope of saving themselves. Certainly discovering the escape would have begun a sort of manhunt but, between the risk of being taken over again, as had happened to others, and almost real death, there would been no hesitation nor proportion: it was worth still groped! And so it was that the group slipped down stealthily from the field from a hole in the net, eluding the surveillance of the sentinels, reached the woods and then started to run to the bushes and weeds, to the increasingly dense vegetation. Although exhausted and malnourished they unanimously decided the guard duties so that they could indulge in a half-sleep for a couple of hours.

They walked for hours and days and dawn of one of these, to their surprise, they discovered that the line was becoming almost a reality: “We did it guys!”

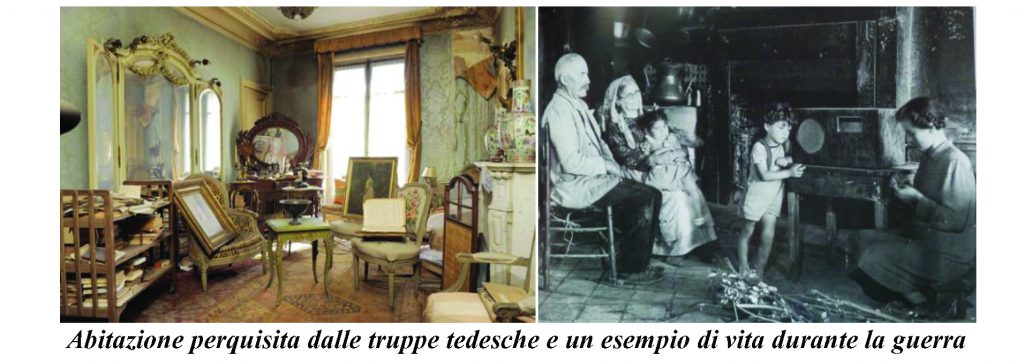

The first autumn snow had helped them. The tracks were covered by the snow. They headed towards the Italian border. Then they passed through solitary and impervious streets between the ridges of the mountains, finding even help from a peasant family who gave them food and rest, and whose good sense saved them from the fascist madness. The border was very close. By now they were arrived in Bolzano but their war was not over yet: they were in fact in a lacking security area because it hadn’t been yet liberated by the Allied forces. Then no one knew anything about the fate of the other men of the camp. The group then broke up, my grandfather and his brother in law finally managed to reach Tuscany and others in other places. They were returned on foot to their houses, passing through down the banks of Como lake. Here they stopped and were received in secret by local families for a few days. My grandfather continued with his vivid story especially telling me how hard life was at that time, of how people were living in fear of being found and how all the families were living in their villages with a few coins. Those coins were small treasures. He told me that most of the families living there on the lake were use to hide them in bags tied with long cords and then thrown into the lake from the windows of the houses, to prevent that they could be found then by the Germans during their raids into the poor houses of the local people, or by fascist squads who could take everything they could find nearby, and then to sell all on the black market. Bags with a few coins but with great meaning: they could bring a family to life, from dawn to dusk. Now Oscar, for his deep knowledge of the history of the Como area, opened his eyes and stunned he told me that often, during his diving into the lake, he found several jute bags tied with a rope, empty for the most part but other times there were found a few coins of the time. Unaware of all this story he then linked the facts and thus was born the idea of being able to find a written record of what had been told to me by my grandfather and of what Oscar had found.

The first autumn snow had helped them. The tracks were covered by the snow. They headed towards the Italian border. Then they passed through solitary and impervious streets between the ridges of the mountains, finding even help from a peasant family who gave them food and rest, and whose good sense saved them from the fascist madness. The border was very close. By now they were arrived in Bolzano but their war was not over yet: they were in fact in a lacking security area because it hadn’t been yet liberated by the Allied forces. Then no one knew anything about the fate of the other men of the camp. The group then broke up, my grandfather and his brother in law finally managed to reach Tuscany and others in other places. They were returned on foot to their houses, passing through down the banks of Como lake. Here they stopped and were received in secret by local families for a few days. My grandfather continued with his vivid story especially telling me how hard life was at that time, of how people were living in fear of being found and how all the families were living in their villages with a few coins. Those coins were small treasures. He told me that most of the families living there on the lake were use to hide them in bags tied with long cords and then thrown into the lake from the windows of the houses, to prevent that they could be found then by the Germans during their raids into the poor houses of the local people, or by fascist squads who could take everything they could find nearby, and then to sell all on the black market. Bags with a few coins but with great meaning: they could bring a family to life, from dawn to dusk. Now Oscar, for his deep knowledge of the history of the Como area, opened his eyes and stunned he told me that often, during his diving into the lake, he found several jute bags tied with a rope, empty for the most part but other times there were found a few coins of the time. Unaware of all this story he then linked the facts and thus was born the idea of being able to find a written record of what had been told to me by my grandfather and of what Oscar had found.

So we got straight to work immediately. After a few weeks some interesting stories told by the people of that period who still remembered what we were experiencing, showed up into the immense and untangled internet network. Here is the evidence we were looking for and are now here!

So we got straight to work immediately. After a few weeks some interesting stories told by the people of that period who still remembered what we were experiencing, showed up into the immense and untangled internet network. Here is the evidence we were looking for and are now here!

ELIA LISTENS TO CATERINA: In 1943 I was 15 years old. Those were bad times, there still was the war between partisans and fascists, the boys under 18 were loaded on freight trains, and once they arrived at final destination some of them were shot while others put to forced works, with the German guards behind them, and prisoners were often left with nothing to eat. Around the end of the war Germans started to deport also women and children. There was no food and to get it you had to give a label to the store, there was no money and the little money we had was all hidden in small bags of canvas and tied with a piece of rope and then thrown down in the lake for fear that the Germans could be able to take it away from us.

In the school there were not many teachers, and at age 15 we already went there no more. The only entertainment was the long walks. During the war there were fascists who were selling food at very dear price and they were called “the black bag”. We had no shoes nor clothes then we tried to manufacture them by ourselves and packing at home, there was the cobbler for shoes but to not to spend too much money we used to make by ourselves some linden wooden clogs. Older people always wore white and black pants of striped cotton and they used them all the year while women were forbidden to wear them: they usually wore dark aprons cotton; those who had sheep were spinning wool and making sweaters, socks, hats and scarves. To get not only white garments some acorns of Carpano plants were boiled so that wool to be dyed could be dipped into that boiled water. To get to and from the lake to the country we usually used the donkey, with the sled to transport goods. I realized that the war was over because all the bells were ringing and people exulted in the country and there was only one radio which was soon put at the window so that everyone could go and listen to all the information about the end of the war .

DAVIDE RUSCONI LISTENS TO ELENA GRASSELLI: I lived in constant tension and concern in the period of the war because the information was few and many times I was feeling a pang at my heart in this interminable waiting for the end of a war of which I could not understand the reasons. I wrote a lot of letters to my future husband who still was in the work camp, but the answers I got were very few, although sometimes they were reassuring me. because I was sure he was still alive! I was making part of the Resistance Committee when I was 25 years old and I think I was the first woman in Torno (CO) who became aware of the impending liberation of our country. Fortunately, my parents worked here in Torno, in a butcher shop and delicatessen, and we could afford something more than the miserable food imposed by the annual card. Everything was controlled by the Germans: you could buy 1 hg of bread and 20 g of margarine per day, and the little money I was earning was then all hidden in a jute cloth, strictly bound with a rope and then thrown into the lake, in certain defined places, so that we could prevent that someone could find it and take it away in the possible and continuous fascist and German raids.

DAVIDE RUSCONI LISTENS TO ELENA GRASSELLI: I lived in constant tension and concern in the period of the war because the information was few and many times I was feeling a pang at my heart in this interminable waiting for the end of a war of which I could not understand the reasons. I wrote a lot of letters to my future husband who still was in the work camp, but the answers I got were very few, although sometimes they were reassuring me. because I was sure he was still alive! I was making part of the Resistance Committee when I was 25 years old and I think I was the first woman in Torno (CO) who became aware of the impending liberation of our country. Fortunately, my parents worked here in Torno, in a butcher shop and delicatessen, and we could afford something more than the miserable food imposed by the annual card. Everything was controlled by the Germans: you could buy 1 hg of bread and 20 g of margarine per day, and the little money I was earning was then all hidden in a jute cloth, strictly bound with a rope and then thrown into the lake, in certain defined places, so that we could prevent that someone could find it and take it away in the possible and continuous fascist and German raids.

Then I also worked at “Saprai”, an office which carried out disposal of food. In that way I could receive the vouchers useful to buy several sacks of flour which then I could send secretly to the partisans who were still in Valsassina or in its surroundings areas. All this was done in the great secrecy because a German command was stationed near Sant’Agostino (Como) and wanted to know every detail of the situation. Although I met a man, a German, with a bad Italian pronunciation, who told me how much he was suffering for himself but more for his wife and children remained in Germany. This shows that everyone was forced to live this terrible situation and fight with no reason, since the suffering of the allies or the enemies was the same. We could listen to the radio only when it was possible and any communication was coming only from England. I waited anxiously for the return of my boyfriend and finally I could reach him, on August 27th of ’45, in Como, and the immense joy I felt in seeing and embracing him was indescribable and still today I feel the same emotion when I tell about that…

ELIZABETTA LISTENS TO MARTINA: Martina was 20 years old in 1945. At that time women were forced to donate their “GOLD WEDDING RING” that the Italian State was asking them. The Duce had forced entrepreneurs of that time to wear a black shirt while boys had to wear black pants and white shirts to do gymnastics. The girls had to be dressed in a white shirt and black skirt. DUX FIELD was a camp of boys. All the girls had to go to the Como Stadium to put themselves in line to form the word DUX = Duce, or sometimes they all were gathered in front of the beam house (today is called Terragni Palace), where they could listen the Duce’s speeches. Some friends of my grandmother were studying languages at the Berlitz school in Como. In this school the alarm was sounded often to warn that foreign planes would have come to bomb that area, so that the girls could then have had an escape. There was the ration card, with which we could buy various kinds food, such as sugar, flour, bread. However, clothing was purchased according to our own financial resources. The shoes were heeled cork or hooves. I remember that a lot of people were use to hide money, coins and the few jewels remained from family memories, in some small bags tied with a rope and then they got thrown them in the lake, in secret places, where then they were fished out. People were afraid that fascists could bring them away their meager belongings during the raids. In 1944, school lessons were suspended because of the war and students of the last classes had to postpone the exams. One day an allied tank passed and stopped in Lezzeno: there were African soldiers. On that van was sitting a lady who was helping the Italian army. A boat that had passengers on board was strafed on the lake located between Bellagio and Tremezzo, and nearby also the Grand Hotel in Tremezzo was bombed. Benito Mussolini and Claretta Petacci were executed in Giulino Mezzegra, while their closest followers, called “hierarchs”, tried to escape towards Switzerland. Then the 25 of April was commemorated in public squares with singing and waving flags.

ALICE CASTELNUOVO AND FRANCESCA LISTEN TO FRANCESCO FRANCHI

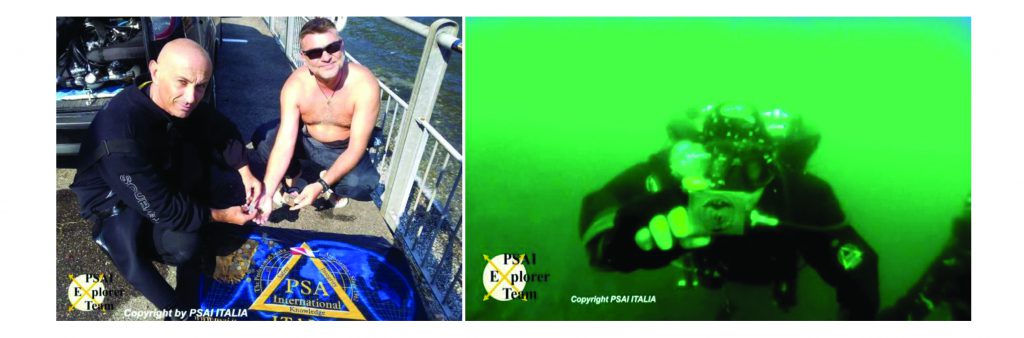

In 1943 I went to hide me in the mountains with my five fellow villagers, but the police then found us and brought to Milan: the city had been bombed apart from the cathedral. Then I fled alone over the mountains. There was no food so my father was coming to bring me the soup, at night we could not turn on the lights and I was often forced to sleep on the trees because if the Germans would have found me they would have kill me. The Germans came and took away the cattle and all the clothes and searched the whole house in search of coins and jewelry that luckily we had put earlier in some small pockets tied with a long rope and thrown in the lake. Thus it was that they could not take away the little money we had so we were able to eat something for a certain period, thanks to those coins. Then they arrived in the neighboring countries and they captured some of the partisans who were on the “Lemna Alps”. They also captured some of my fellow villagers and brought them to Germany for three years. The Americans arrived also here in “Faggeto” and the remaining partisans joined to them to fight the Germans. In taverns we could not freely discuss about everything because the Germans were often suspecting that we could have spoken badly of them and even grinding grain was banned! There was the card which was serving to lend us food as 1 kg of bread per week. At the news of the end of the war all the people here became merry and happy. In the streets of our small country there was a great rejoicing. Corroborated by this news, including family memories and historical data and stories by locals and then by the fantastic documentation found on the net (tales of people of the time) we kept the strong desire to continue on this adventure. A lot of times we dived into the lake looking for some small sign of a distant past, and many times we shopped thinking about quitting with such a fruitless research. But we have never lost heart and even more stubborn than ever we continued in researching, we believed until the end and this obstinacy has proved us right. All set in a late summer afternoon we found some interesting things that gave us reason of that we were looking for and rewarded us for all our work and time spent till there, but happy once again to have given birth to a piece of our history.

Croce di al merito di mio nonno Giuseppe

Il Team Explorer PSAI ITALIA:

Il Team Explorer PSAI ITALIA:

Leonardo Canale Responsabile PSAI Italia per le ricerche storiche,

Maurizio Bertini Responsabile PSAI Italia

Oscar Lodi Rizzini: Istructor Trainer PSAI Italia, subacqueo fondista, il naso del gruppo colui che dalle asperità del fondale riesce a trovare indizi interessanti reduce da numerose spedizioni