SS Creemuir Bell Recovery

By Paul Haynes. PSAI Instructor # 264 (www.haynesmarine.com)

During the last of the Autumn days light, as it made its way North along the East Coast of Scotland, at 1700hrs on the 11th November 1940, for the second time that day, convoy EN23 comprising 31 merchant vessels was attacked by German aircraft. The 3990 grt British Steam Ship SS Creemuir was the lead vessel of the port column and despite her defensive 4 inch gun and 2 Lewis machine guns, was struck mid-ships by an aerial torpedo, which exploded directly into the engine room. The damage was obviously fatal so out on the bridge, Captain Mankin calmly ordered “take to the lifeboats”. Less than 3 minutes after being struck, SS Cremuir with most of her crew and Captain slipped below the surface, another casualty of an increasingly brutal war.

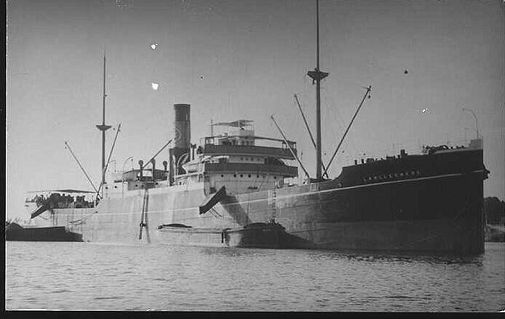

SS Creemuir (former Langleemere, originally named Medomsly)

Convoys under attack had strict orders not to stop and assist stricken vessels for fear of placing their own vessel at greater risk of attack. The remainder of the 2 columns of convoy EN23 therefore steamed on North leaving those in the freezing water to their fate. Of the 42 crew aboard SS Creemuir, only 12 were alive by the time they were picked out of a stormy North Sea by the Dutch merchant vessel SS Oberon later that night.

From Admiralty war loss records, my good friend and dive buddy Rod Macdonald had been aware of the Creemuir for a number of years. However with an approximate position some 15 miles due East of our home town of Stonehaven, Scotland, it was considered too far out into the treacherous North Sea for the small RIBs we typically used for diving back then.

Despite its exposed location, the lure of the Creemuir grew and in 2009, with the safety support of an additional boat, we disappeared over the horizon to find her. After a bumpy ride out and SONAR sweep of the area, the distinctive shape of a large vessel showed up on the echo sounder at a depth of around 75m. Although the identification was unconfirmed, the approximate length of the sea-bed anomaly (350ft) matched that of the Creemuir. Nothing else of this size had been reported sunk in the area so we were confident she had been found.

A week later, a dive team of 6 using 2 RIBs departed Stonehaven and after a short confirmatory search, an hour later we were above the shipwreck. For additional safety, as we waited for the tide to stop running a shot-line was deployed at each end of the wreck providing the option of 2 ascent routes. At the moment of slack water we slipped over the sides of our respective boats and began our descent. However, much to my frustration, at 40m the hand set display of the CCR I was diving failed. I bailed out to open circuit and advised Rod that I was ascending and that he and the third diver in our team Tony Ray should continue the dive. Surfacing a few minutes later I de-kitted and was helped back aboard the RIB.

Forty-five minutes later the rest of the dive team began to arrive at the surface earlier than expected. Despite being 15 miles offshore where clearer water is more likely, conditions sub-surface were very disappointing with no daylight penetrating the turbid water. In total darkness and 1m visibility, little exploration could be safely undertaken at 70m amongst the wreckage they had landed upon and so the dive was cut short – there would always be another opportunity to return when conditions had improved.

With so much other virgin wreck diving taking place off the East coast of Scotland by our group, the Creemuir was put to one side for the time being. However Rod made a posting on his authors web-site regarding our dive and was subsequently contacted by a Mr Noel Blacklock, former SS Creemuir Radio Officer who believed himself to be the last living survivor of her sinking.

At 90 years of age Noel was still a spritely fellow with a very sharp mind and provided a clear picture of the Creemuir’s sinking and the subsequent rescue. Watching the 4 inch stern gun slip below the water he was briefly knocked unconscious. Fortunately he was supported by his life vest and upon regaining consciousness, whilst swimming for his life, on turning around his last memory of his ship was a striking image of her bows, foredeck and bridge standing vertically against the evening sky as she slid backwards onto the sea.

A few months after contacting Rod, on his way to the Shetland Isles for a holiday, Noel and his wife Muriel stopped off at Aberdeen to meet Rod and gave permission for his detailed personal account of the Creemuir sinking to be included in Rod’s then latest book The Darkness Below, a recommended read for any technical wreck diver (www.rod-macdonald.co.uk).

Early 2012 Rod and I purchased a larger 7m RIB with a good offshore sea keeping hull design plus a new 150HP Yamaha outboard engine (www.haynesmacdonaldservices.com). With a larger dive boat that was UK Maritime Coastguard Agency (MCA) coded and equipped for commercial use, we were now sufficiently confident to venture offshore with a single dive boat.

Rod’s meeting with Noel had reinvigorated our interest in the Creemuir and as a consequence, during the summer of 2012, in the relative comfort and safety of our new RIB, we returned to the Creemuir. On the first return dive Rod was boat handling so I dived with Gary Petrie and Greg Booth.

In stunning 20m visibility and ambient light we landed at 75m on the collapsed hull plates of the aft hold. Not knowing the ‘lay of the land’, at this point we headed towards the obvious large structure to our left. This proved to be the stern section standing over 12m off the sea-bed but rolled onto its port side. I rode my DPV aft and noted the rear 4 inch gun was still in place and elevated as if ready to engage an unseen enemy. I continued around the stern past the propeller and rudder, over the fallen aft mast and returned to the shot-line, periodically pausing to take in as much detail as possible. With bottom time running out, I noticed the indistinct shape of a large structure in the distance and decided to investigate. As I scooted over the collapsed aft hold the image sharpened as the remainder of the shipwreck came into view.

Complete and on an even keel, the rest of the ship appeared intact but had been cleanly severed aft of the rear superstructure fully exposing the engine room and rear superstructure. It was now apparent that the wreck was in 2 parts, no doubt as a result of the weakness created by the torpedo damage and the stress placed upon her hull during the sinking. Being unattached to the main forward section of the ship explained why the hull plates of the aft hold had collapsed down to sea-bed level. I scootered up past the exposed engine room peering into the gloom at the catwalks that surrounded the large engine and up into the starboard side superstructure corridor. Moving onwards through the corridor past the galley with intact crockery littering the floor and forward past other rooms I slowly scooted my DPV out of an open doorway onto the deck aft of the bridge, where once stood the funnel. With the bridge immediately to my front but planned bottom time having now long expired, I reluctantly cut short any further exploration, turned and scooted aft over the engine room pitched roof towards the port side and out over the clean break free ascending on my scooter as I returned to the shot-line clearly distinguished by our flashing strobes in the distance. Additional decompression had been incurred but worth it to gain the added appreciation of the how the wreck lies, which would help facilitate further exploration.

Having established a personal relationship with the last living survivor, Rod and I had already decided that should we find the ships bell, it would be presented to Noel. Following a few days of fantastic virgin shipwreck diving in the 70m – 100m range off Rattry Head, NE Scotland with our good friends Buchan Divers, we returned to the Creemuir.

On the third return dive I had a particular focus on finding the bell and spent the whole bottom time rummaging around the forward section / bows. With little to show for my efforts I watched Rod and Jim Burke signal they were commencing the ascent. Knowing I had to follow them I swam onto the forecastle, which due to the partial collapse of the forward hold is now bent back on itself at a 45 degree angle. Desperately scanning the area again, I was about to call it a day when under a web of pipework I noticed the unmistakable shape of a ships bell! However I was out of bottom time and believing I was following them, Jim and Rod where already some 15m above me. I therefore quickly wrestled it from behind the pipework, dragged it up to the bows and securely positioned it. Knowing its exact location, I’d be back soon to lift it.

In marginal conditions Gary volunteered to cox and took us out the following day. In sharp contrast to the 20m visibility the day before, visibility was reduced to a couple of metres but having precisely pre-positioned the bell, Rod and I quickly re-located and sent it up under a lift bag. Conditions were poor on the wreck and known to be deteriorating top-side so we ended the dive and began the ascent. After a short 30 minute deco, forty-five minutes later we were slowly beating a path for an hour back to our homeport against a very heavy sea and increasing head wind but delighted that the bell had been recovered.

After reporting our salvage to the UK Government Receiver of Wreck (a legal requirement), the bell was cleaned up and I made a wooden stand for it. Bearing the original name of the ship SS Medomsly, Noel was contacted and notified that we would be visiting in the near future and that we had a surprise for him.

Unfortunately it has taken all year to get a suitable date for Rod and I to both be free to travel down to England where Noel lives. Finally then , last month we travelled the 500 miles South to the town of Bedford, North of London and after presenting Noel with the bell, took him and Muriel out for dinner. The following day, after a visit to the nearby Bletchley Park Museum, site of the secret WWII British code breaking department, we returned home to Stonehaven.

Rod Macdonald (left), Noel Blacklock (centre), Paul Haynes (right)

To sit with Noel for a few hours listening to his account of the war was a rare privilege and a delight – he survived another sinking following a convoy collision off Iceland! Such privileges are now becoming increasing rare as the number of WWII veterans rapidly declines. Soon the opportunity to make such personal connections with the shipwrecks we find and listen to first hand accounts will be sadly lost.

As a result of enemy action, during WWI and WWII over 10,000 merchant vessels are believed to have sunk around the UK alone. The ordeal and losses suffered by the merchant navy unfortunately does not receive the same level of acknowledgement as that of the armed navies. Let us then never forget that this wonderful sport we enjoy is in part only possible as a result of untold suffering and sacrifice by a generation who faced challenges on a scale incomprehensible to most of us alive day – a world engaged in total warfare. Where ever you may be in the world and regardless of what national allegiances you may hold, please remember to honour their memory by paying due respect to what is frequently a seaman’s final resting place and often who’s sacrifice has allowed us to enjoy the freedoms we take for granted today. Thank you Noel and to all who played their part.

Safe diving.

Paul